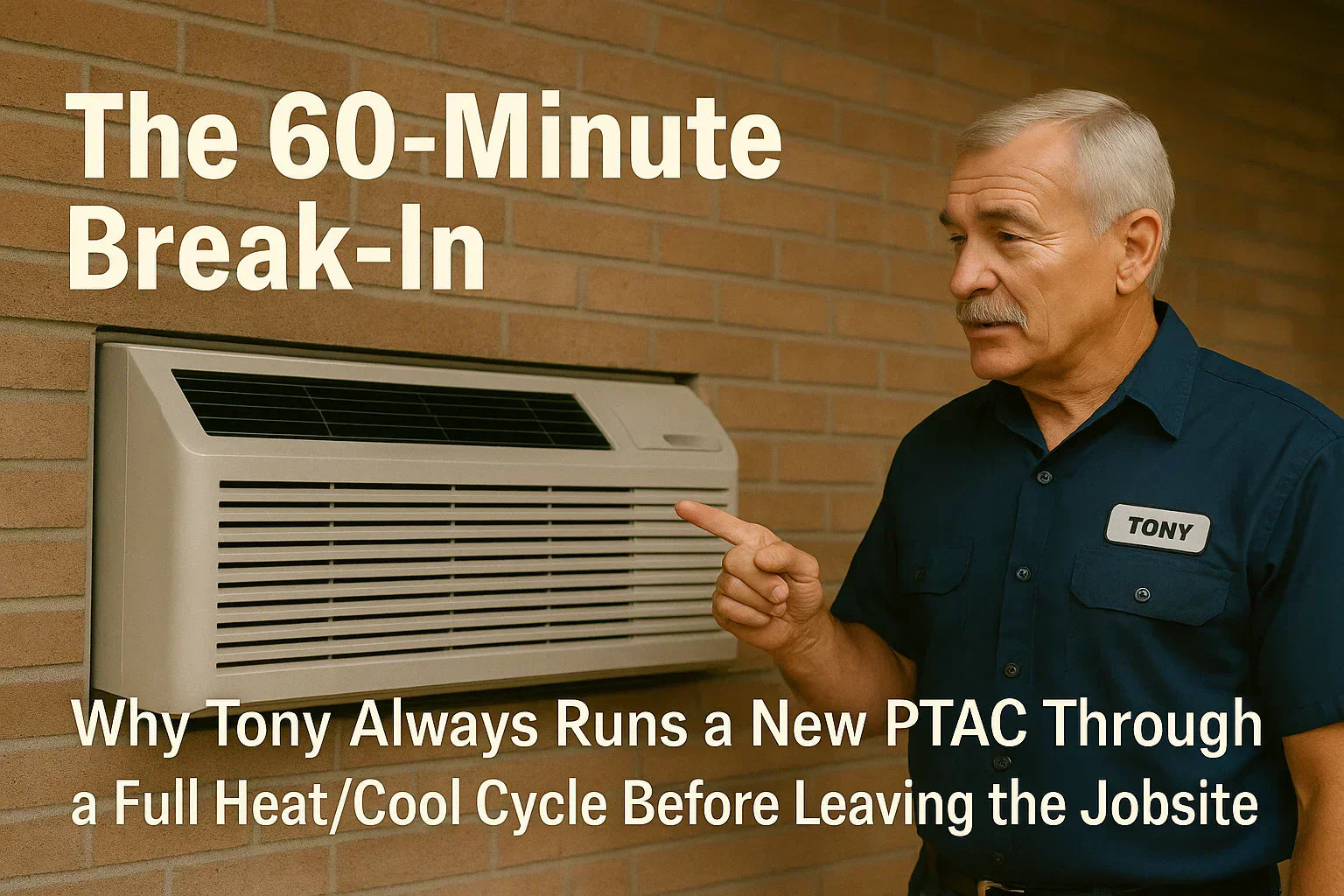

By Tony Marino — “If you don’t test it now, it’ll fail when the customer’s asleep.”

🕒 1. The Hard Truth: Most PTAC Problems Show Up in the First Hour

You can install a PTAC perfectly — sleeve square, drain pitched, weather seals tight, wiring torqued — and still send the system off to fail within 72 hours.

Why?

Because most unseen problems don’t happen during installation.

They happen during operation:

-

Bad control board handoff

-

Sensor error

-

Compressor thermal trip

-

Heat-strip surge

-

Defective fan relay

-

Factory-set blower calibration

-

Refrigerant migration

-

Drain pan leveling

-

Sleeve pressure issues

-

Exterior grille back-pressure

-

Weatherseal turbulence

-

Motor resonance

-

Loose connectors from shipping

These NEVER reveal themselves until the PTAC:

-

Heats

-

Cools

-

Cycles

-

Stabilizes

-

Defrosts

-

Equalizes pressure

And that takes time.

That’s why Tony never leaves a jobsite until he’s run a full 60-minute break-in cycle.

It’s not optional.

It’s not “nice to do.”

It’s how you ensure the install won’t fail tonight.

Amana Distinctions Model 12,000 BTU PTAC Unit with 3.5 kW Electric Heat

Let’s break it down.

🔧 2. What Is the 60-Minute Break-In? (Tony’s Definition)

The “break-in” is a complete testing sequence where Tony forces the PTAC to run:

✔ Heat mode

✔ Cool mode

✔ Fan-only mode

✔ Full-speed blower

✔ Reverse-air pressure under load

✔ Heat-strip + compressor transition

✔ Thermostat cycling

All while monitoring:

-

Amp draw

-

Voltage under load

-

Temperature split

-

Condensate drainage

-

Pressure stability

-

Noise curve

-

Airflow direction

-

Grille vibration

-

Sleeve resonance

-

Thermal equalization

This isn’t a “turn it on and walk away” test.

Tony pushes the unit through every condition it will face in real life.

He wants the system to FAIL before he leaves — so the customer never experiences the failure themselves.

🔥 3. Why 12k PTAC Units Need Break-In More Than Any Other Size

A 12,000 BTU PTAC (especially with a 3.5 kW heat kit) is the most sensitive size for three reasons:

🌀 1. Highest airflow pressure

12k PTACs push 350–420 CFM.

That makes them sensitive to:

-

Sleeve misalignment

-

Grille back-pressure

-

Air leaks

-

Foam intrusion

-

Furniture obstruction

🔥 2. Largest heat-kit load

A 3.5 kW heat kit draws 14.5 to 17 amps depending on voltage.

If wiring, lugs, or disconnect boxes aren’t perfect, the unit will:

-

Overheat

-

Trip

-

Burn the contactor

-

Short-cycle

-

Smell like burning dust for days

Break-in reveals these loads.

❄️ 3. Sharpest temperature swings

Larger PTACs cause:

-

Rapid discharge temp rise

-

Fast coil cooling

-

Hard compressor starts

-

Strong pressure changes

Improper drain slope, sleeve pitch, or grille airflow becomes instantly obvious during the break-in.

🎧 4. Tony’s Motto: “The PTAC will tell you what’s wrong — if you give it enough time to talk.”

During the break-in hour, Tony listens for:

-

Low-frequency hum

-

High-frequency whine

-

Grille flutter

-

Coil boiling

-

Condensate splash

-

Negative pressure whistling

-

Compressor rattle

-

Blower resonance

-

Internal relay chatter

-

Heat-strip crackle

-

Control board ticking

Each sound = a specific, diagnosable issue.

The first hour is the only time you hear these sounds BEFORE the room gets occupied.

⚡️ 5. Step-By-Step: Tony’s Full 60-Minute Break-In Procedure

This is the exact process Tony uses — the same one that prevents 95% of customer callbacks.

🔥 Step 1 — Run HEAT for 20 Minutes

This tests:

-

Heat-strip load

-

Voltage drop under heat

-

Blower RPM stability

-

Sleeve pressure expansion

-

Weatherseal heat expansion

-

Grille contraction noise

-

Drain pan thermal behavior

-

Thermostat anticipator behavior

Tony checks:

✔ Supply temp: 95–115°F

Lower = voltage drop

Higher = overheating or airflow restriction

✔ Amp draw: 14.5–17 amps

Higher = airflow restriction

Lower = voltage starvation

✔ Blower volume

Should NOT surge up and down.

Fluctuation = blower board calibration problem.

✔ Smells

Burnt dust = normal

Burnt plastic = not normal

Hot electrical smell = immediate shutdown

❄️ Step 2 — Run COOL for 20 Minutes

This reveals:

-

Refrigerant charge defects

-

Coil freeze risk

-

Drain pan overflow

-

Condenser airflow restriction

-

Sleeve pressure turbulence

-

Negative pressure zones

-

Grille misalignment

Tony checks:

✔ Temp split: 15–22°F

Under 14°F = low charge or airflow restriction

Above 25°F = coil freeze risk

✔ Condensation flow

Should drain outward within 1–3 minutes

Backflow = bad sleeve pitch

✔ Compressor noise

Should be steady

Rattling = loose hardware

Buzzing = voltage sag

Knocking = defective compressor

✔ Water movement

Sizzling, popping, or pan splash = bad drainage geometry

🌀 Step 3 — Run FAN ONLY (High & Low)

Fan only mode exposes:

-

Sleeve resonance

-

Grille noise

-

Pressure harmonics

-

Air leaks around foam

-

Blower wheel imbalance

-

Furniture obstruction airflow

Tony checks:

✔ Airflow path

Does it reach the bed?

Does it hit a dresser?

Does it bounce off curtains?

✔ Noise curve

Steady = good

Wobbling = sleeve distortion

✔ Vibration

If the grille vibrates at certain RPMs → sleeve is warped.

🔄 Step 4 — Cycle HEAT → COOL → HEAT

This is the most important part.

Why?

Because transitions cause:

-

Thermal shock

-

Pressure equalization

-

Relay switching

-

Contact arcs

-

Sensor calibration

-

Coil stress

-

Condensate surges

If something’s going to fail early, THIS is when it happens.

Tony checks:

✔ Board response

Any delay > 2–3 seconds = bad relay

✔ Compressor restart

Should NOT hard-start

Hard-start = bad capacitor

✔ Airflow drop

If blower dips during transition → voltage sag

✔ Sizzling in drain pan

Indicates drainage restriction

🧪 Step 5 — Power Cycling + Reset Test

Tony kills power at the disconnect for 30 seconds.

Then he restores power.

This reveals:

-

Board boot issues

-

Thermostat memory problems

-

Stuck relays

-

Faulty safety switches

-

Control board defects

-

PTAC with bad internal capacitors

If a PTAC struggles to restart after power loss, it WILL fail during thunderstorms.

🌡️ Step 6 — Thermal Equalization (The Last 10 Minutes)

By minute 50–60, the unit has:

-

Heated the sleeve

-

Cooled the sleeve

-

Expanded materials

-

Contracted materials

-

Filled the drain pan

-

Pressurized the chamber

-

Stabilized blower RPM

-

Equalized refrigerant

This is the moment where the sleeve either proves it was installed right or shows every flaw.

Tony checks:

✔ Final noise level

Should be steady — no new rattles

✔ Final airflow pattern

Must be consistent across room

✔ Final temperature stability

Thermostat should NOT swing 3–5 degrees

✔ Final water output

Drain pan should NOT have standing water

If ANYTHING fails here, the PTAC is not ready for occupancy.

🔍 6. What the 60-Minute Break-In Catches That Installers Always Miss

Here are real examples.

❌ Blocked drain weep holes

Happens on 30% of installs.

Break-in exposes:

-

Backflow

-

Pan splash

-

Sleeve overflow

❌ Misaligned blower wheel

You won’t hear it for first 10 minutes.

At 40 minutes?

It screams.

❌ Bad heat-strip contactor

Only arcs during sustained heat load.

Break-in catches the early arc.

❌ Negative pressure back-drafting cold air

Cool mode reveals it instantly.

❌ Grille turbulence noise

Fan-only at high speed makes it obvious.

❌ Sleeve warping from bad foam

Heat → expansion → noise → airflow restriction.

❌ Thermostat miscalibration

Heat→Cool transitions expose short-cycling.

❌ Compressor fails under repeat restarts

Break-in stress-tests it.

❌ Voltage sag under full load

Heat mode exposes dip to 208–212V.

❌ Factory defects

Bad sensors

Bad boards

Bad relays

Bad transformers

All caught before you leave the jobsite.

🏚️ 7. The Cost of NOT Doing a Break-In (Tony’s Real Callbacks)

Here’s what Tony has had to fix because installers didn’t run a break-in:

-

Melted heat-strip wiring

-

Compressor failure in 48 hours

-

Flooded carpet from condensate backflow

-

Sleeves pitched backward

-

Screaming blower wheels

-

Louvers fluttering at 300 CFM

-

Thermostat short cycling

-

Circuit breakers tripping at night

-

Cold spots from furniture obstructions

-

Negative pressure pulling in outdoor air

All of these problems showed up within the 60-minute window — and the installer missed them.

📚 8. External Verified Resources Supporting the Break-In Concept

Here are reliable resources that align with best practices mentioned in this guide:

-

Energy.gov – Air Sealing Guidelines

https://www.energy.gov/energysaver/air-sealing-your-home -

OSHA – Construction Saw Safety (for proper wall cuts)

https://www.osha.gov -

International Building Code (Wall Framing Requirements)

https://codes.iccsafe.org/ -

UL Guidelines for Electric Heat Components

https://ul.com/ -

ASHRAE Handbook – HVAC Fundamentals (Airflow & Pressure)

https://www.ashrae.org/technical-resources/ashrae-handbook

These sources firmly support operational load testing as a commissioning requirement.

🏁 Final Word From Tony

Most installers think the job ends when the PTAC slides into the sleeve.

Nope.

The job ends when the PTAC:

-

Heats

-

Cools

-

Drains

-

Cycles

-

Stabilizes

-

Holds pressure

-

Maintains control

-

Proves it’s ready

“The unit doesn’t work because you installed it.

It works because you TESTED it.”

The 60-minute break-in is how you eliminate surprises.

It’s how you prevent callbacks.

It’s how you deliver a system that won’t fail on the customer at 2 AM.

And that’s why Tony never — EVER — leaves the jobsite until the PTAC has passed its first hour of life.

Buy this on Amazon at: https://amzn.to/3WuhnM7

In the next topic we will know more about: Why Tony Always Adds a Temporary Support Rail — The One Trick That Saves You From a Crooked Install