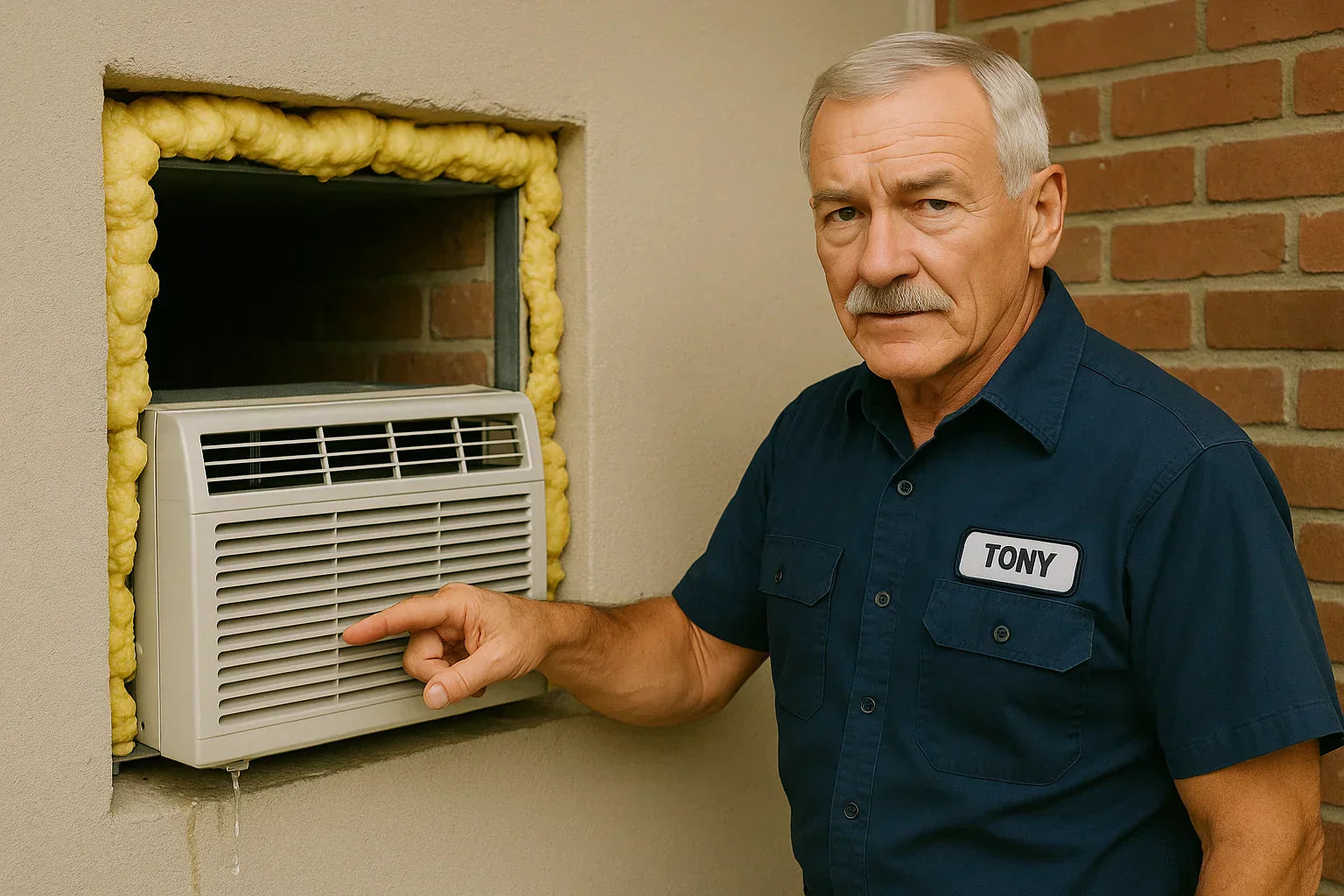

By Tony Marino — “If the condensate doesn’t know where to go, it will choose the worst place possible.”

Every PTAC installer talks about cooling.

Some talk about noise.

A few even talk about electrical.

But almost nobody talks about condensate pathways — and that’s why so many homes, hotels, and apartments end up with:

-

Squishy carpets

-

Rotten baseboards

-

Mushy drywall

-

Mold streaks under the PTAC

-

Waterlogged insulation

-

Swollen flooring

-

Musty smells

-

Complaints that “the AC leaks”

Let me tell you something from 35 years of crawling behind units:

A PTAC doesn’t leak.

It drains — somewhere.

Either down a proper slope…

Or across the floor you’re billing your customer to protect.

If you don’t give condensate a predictable exit path, you’re basically pushing warm, humid air into a muddy hole and hoping physics takes the night off.

It won’t.

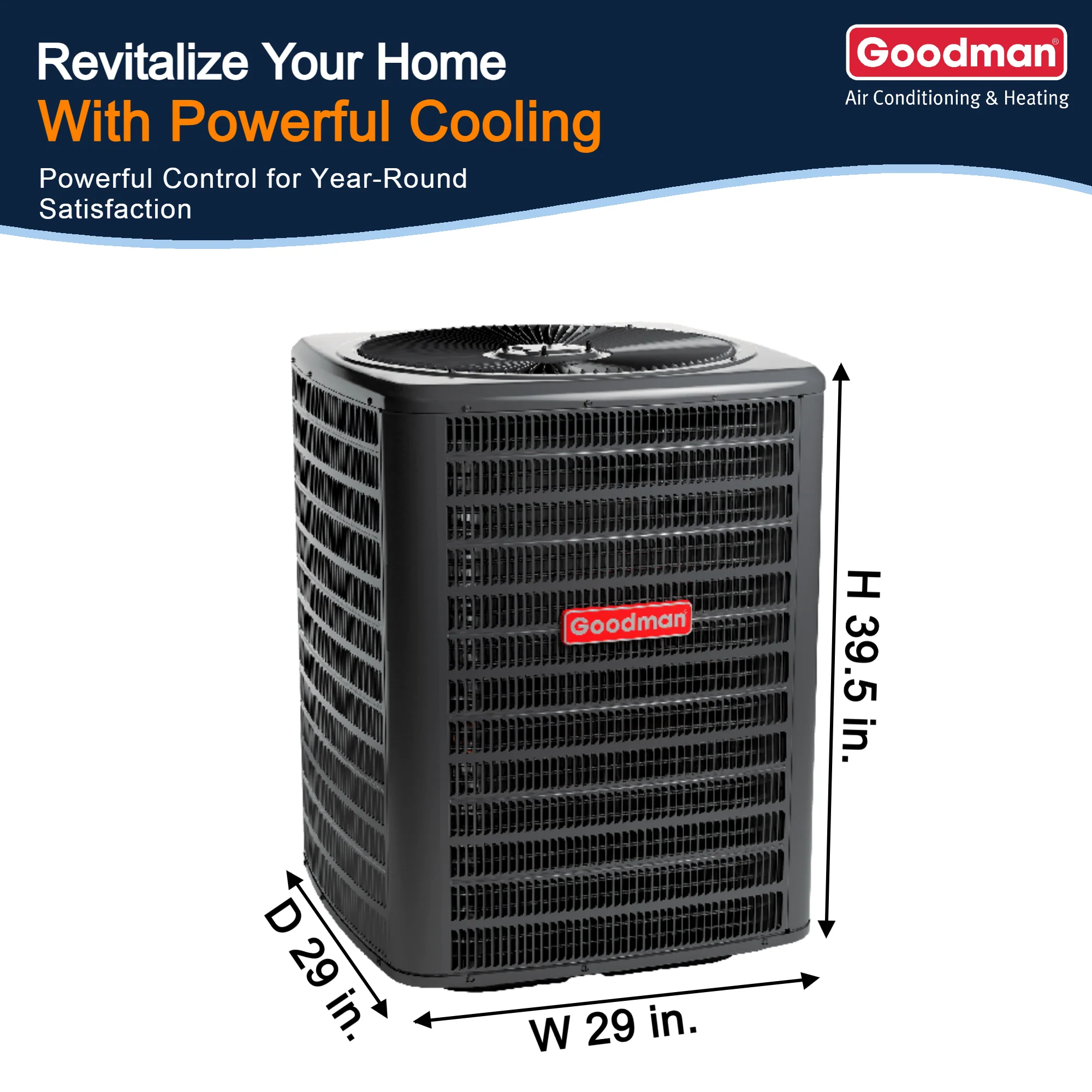

Amana Distinctions Model 12,000 BTU PTAC Unit with 3.5 kW Electric Heat

This article is the no-nonsense, field-tested guide to preventing indoor water damage from PTAC condensate — the Tony way.

💧 1. Condensate Isn’t a “Maybe” — It’s a Guarantee

A 12,000 BTU PTAC will remove anywhere from 0.8 to 1.5 gallons of water per hour on a humid day.

That’s 10–18 gallons per 12-hour run cycle.

And if you think that water magically disappears, you’re dreaming.

Every drop has to:

-

Form on the coil

-

Run down into the drain pan

-

Flow into the correct channel

-

Follow the sleeve slope

-

Exit through the weep holes

-

Pour outside safely

If ANY part of that chain is wrong — and I mean the slightest little hiccup — the water takes the path of least resistance:

Into your room.

That’s the “muddy hole” — the indoor space that ends up soaking because the installer didn’t think like water.

🧠 2. Tony’s First Rule of Condensate: “Water Does What It Wants, Not What You Wanted.”

Every installer means well.

But water doesn’t care about intentions — it obeys:

-

Gravity

-

Capillary action

-

Air pressure

-

Surface tension

-

Material absorption

If you fail to respect a single one of those forces, you get:

-

Edge wicking

-

Backflow

-

Siphoning

-

Pan overflow

-

Slow leak-ins

-

Hidden buildup behind the sleeve

-

Mold growth inside insulation

-

Dripping from the front of the unit

People think a PTAC leak is dramatic.

It’s not.

The real danger is the slow leak that ruins a floor over 2–6 months before anyone notices.

🧱 3. Why Warm Air Makes the Problem Worse (The Muddy Hole Effect)

Warm air hitting wet, porous material = disaster.

Here’s why:

A. Warm air boosts evaporation

That moisture doesn’t disappear — it moves into:

-

Drywall

-

Carpet backing

-

Wood flooring

-

Base trim

-

Furniture feet

B. Evaporated moisture increases humidity

Humidity condenses again — deeper into the structure.

C. The PTAC tries to remove that humidity

So it runs more.

And makes more condensate.

D. The cycle repeats

Until an entire wall system is saturated.

Warm air isn’t just “heat.”

It is a multiplier for water damage.

If you run a PTAC with poor drainage, you’re literally forcing warm, moist air into a wet cavity and accelerating the damage.

That’s the muddy hole.

🛠️ 4. How Condensate Is SUPPOSED to Move Through a 12k PTAC Sleeve

Here’s the anatomy of a proper drain path.

✔ Water forms on the evaporator coil

✔ Drips into the primary pan

✔ Passes through the molded drain slot

✔ Hits the sleeve floor

✔ Runs downhill

✔ Finds the sleeve weep holes

✔ Exits the building

If the sleeve slope is wrong — even slightly — the whole thing breaks.

Let me be clear:

A PTAC sleeve must slope ¼" downward toward the outdoors.

No exceptions. Not ⅛". Not “eyeballed.” Not “close enough.”

⅛" will fail on old buildings.

0" will fail everywhere.

Reverse slope will destroy everything.

📐 5. Tony’s 6-Point Sleeve Slope Check (Zero Guesswork)

I don’t “trust” level.

I verify level.

Here’s my 6-point test:

① Place a digital level at the front-left corner

Should read sloping outward.

② Place it at the front-right corner

Same.

③ Place it at the center

If the center bows upward, water pools.

If it bows downward, the chassis binds.

④ Place it on the back-left

This confirms twist or torque in the sleeve.

⑤ Place it on the back-right

If this corner is higher than the front, you will have backflow.

⑥ Pour 4 oz. of water and time the exit

Under 5 seconds = good.

5–15 seconds = marginal.

15+ seconds = sleeve problem.

No flow = disaster.

Most installers never perform test #6.

That’s why customers end up with wet carpet and a bad review to go with it.

🧰 6. The #1 Cause of Condensate Problems: Foam In the Wrong Place

Spray foam is the devil when used wrong.

I’ve seen:

-

Blocked weep holes

-

Blocked sleeve slopes

-

Blocked pressure relief channels

-

Blocked chassis drain paths

-

Water wicking backward into insulation

-

Foam acting like a sponge

-

Foam swelling and reversing the sleeve slope

If foam expands inside the sleeve, the PTAC will ALWAYS leak.

Foam is for gaps around the sleeve.

Not for inside the sleeve.

Not for under the sleeve.

Not for behind the sleeve.

If you wouldn’t spray foam inside your ductwork…

Don’t spray it inside your PTAC sleeve.

🔎 7. How Weather Seals Cause Condensate Misery (If Installed Wrong)

Weather seals are critical — but dangerously easy to misuse.

Here’s what goes wrong:

❌ Sealing over the drain path

Blocks exit flow.

Water overflows inside.

❌ Sealing the bottom corners

That’s exactly where condensate needs to travel.

❌ Using open-cell insulation

Absorbs water → becomes a wick → slowly transports moisture into drywall.

❌ Using too much sealant

Creates a dam that traps water.

❌ Leaving gaps

Wind pushes rainwater inside the sleeve.

Tony’s rule:

“Seal for air.

Leave room for water.”

Air and water move differently.

Treat them differently.

🌀 8. Negative Pressure: The Silent Condensate Thief

Some PTAC units — especially higher-end 12k models — create small negative pressure zones inside the sleeve.

If the sleeve isn’t sealed correctly, the blower creates suction that:

-

Pulls water back toward the room

-

Lifts water up the sleeve wall

-

Siphons water against the flow path

-

Causes indoor dripping hours after the unit shuts off

Ever see a PTAC drip inside AFTER cooling is over?

Negative pressure did that.

And you can thank the installer.

🧪 9. Tony’s Wet-Baseboard Test (The One Maintenance Staff ALWAYS Misses)

Here’s how I find hidden condensate leaks:

-

Run the PTAC for 20 minutes

-

Turn it off

-

Wait 10 minutes

-

Press the baseboard gently with your knuckles

If it feels:

-

Hollow

-

Soft

-

Mushy

-

Warped

-

Warmer on one side

You’ve got condensate infiltration.

This method catches problems before the wall cavity goes moldy.

🧯 10. My No-Failure Rule: The 4-Path Condensate Commandments

If ANY of these four paths are wrong, you will have water issues.

PATH 1 — Coil to Pan

Clean?

Level?

Unobstructed?

PATH 2 — Pan to Sleeve

No debris?

No foam?

No rust lip blocking flow?

PATH 3 — Sleeve Slope

¼" minimum.

Consistent side to side.

PATH 4 — Sleeve to Exterior

Weep holes open?

Exterior grade lower?

Grille not blocking drainage?

If all 4 paths are correct, the PTAC NEVER leaks.

🔧 11. What Bad Condensate Management Does to Floors, Carpets, and Drywall

Let’s talk REAL damage.

Flooring Damage:

-

Vinyl curls

-

Laminate swells

-

Hardwood cupping

-

Mold under planks

Carpet Damage:

-

Delamination

-

Pad saturation

-

Musty odor

-

Microbial growth

-

Rust stains from tack strips

Drywall Damage:

-

Softening

-

Disintegration

-

Fungal streaks

-

Bubbling paint

-

Baseboard mold

-

Structural compromise

Furniture Damage:

Legs rot.

Veneers discolor.

Drawers swell shut.

This isn’t cosmetic.

This is structural.

All from 1/8 cup per hour of mis-directed condensate.

🧰 12. Tony’s Full Condensate Inspection Checklist (Print This)

Use this checklist before you declare a PTAC “installed.”

✔ Sleeve slope: perfect?

✔ Drain pan clean?

✔ Weep holes open?

✔ Foam outside only?

✔ Weather seals not blocking water paths?

✔ No back-pitch?

✔ No sag in support bracket?

✔ Water test performed?

✔ Grille seated correctly?

✔ Indoor floor dry after test cycle?

If any item fails, the installation fails.

📚 13. External Verified Resources (Condensate, Water Control, Building Science)

Here are reliable resources that align with best practices mentioned in this guide:

-

Energy.gov – Air Sealing Guidelines

https://www.energy.gov/energysaver/air-sealing-your-home -

OSHA – Construction Saw Safety (for proper wall cuts)

https://www.osha.gov -

International Building Code (Wall Framing Requirements)

https://codes.iccsafe.org/ -

UL Guidelines for Electric Heat Components

https://ul.com/ -

ASHRAE Handbook – HVAC Fundamentals (Airflow & Pressure)

https://www.ashrae.org/technical-resources/ashrae-handbook

Each one aligns with the rules I’ve laid down — airflow, water paths, slope, and proper sealing.

🏁 14. Final Word From Tony

If I had to teach only ONE lesson to every PTAC installer in America, it wouldn’t be electrical.

It wouldn’t be airflow.

It wouldn’t even be refrigerant handling.

It would be this:

“Water always wins unless you tell it EXACTLY where to go.”

Because a PTAC doesn’t leak randomly.

It leaks predictably when you ignore condensate physics.

Stop pushing warm air into muddy holes.

Stop trusting “looks good” on the sleeve level.

Stop over-foaming.

Stop blocking drain paths.

Stop installing without testing.

Water damage isn’t an accident — it’s a symptom of lazy installation.

And Tony doesn’t do lazy.

Buy this on Amazon at: https://amzn.to/3WuhnM7

In the next topic we will know more about: Why Tony Cuts 1/8 Inch High on Every PTAC Opening — The Expansion Gap Nobody Teaches but Every Pro Uses