If the words “line set,” “microns,” “subcooling,” or “refrigerant charge” make your eyes glaze over, you’re not alone. Refrigerant work has a reputation for being mysterious, technical, and off-limits—and while parts of it are regulated and best left to licensed pros, understanding the basics makes you a much smarter homeowner.

This guide explains what refrigerant lines do, why charging matters, and how to spot good (or bad) practices, without turning it into a textbook or a licensing exam.

🧠 Big Picture First: What Refrigerant Actually Does

Refrigerant isn’t fuel and it isn’t “used up.” It’s a heat-transfer medium that circulates in a closed loop, carrying heat from inside your home to the outdoors (in cooling mode).

Think of it like a delivery truck:

-

It picks up heat indoors

-

Transports it through the refrigerant lines

-

Drops it off outside

-

Comes back to do it again

If the “roads” (refrigerant lines) or the “load amount” (charge) are wrong, performance suffers—no matter how good the equipment is.

🔗 What Is a Refrigerant Line Set?

A line set is the pair of copper tubes that connect the indoor and outdoor parts of your HVAC system.

The two lines explained simply

-

Suction line (larger, insulated)

Carries cool, low-pressure refrigerant vapor back to the outdoor unit. -

Liquid line (smaller, usually uninsulated)

Carries high-pressure liquid refrigerant to the indoor coil.

If either line is the wrong size, damaged, or installed poorly, the system can’t move heat efficiently.

📏 Line Set Sizing: Why Size Actually Matters

Manufacturers specify exact line sizes for each system capacity. This isn’t a suggestion.

What happens if sizing is wrong

-

Too small → high pressure, noise, reduced capacity

-

Too large → oil return problems, compressor wear

-

Mismatched lengths → incorrect refrigerant charge

Always match:

-

system tonnage

-

approved line diameters

-

maximum and minimum line lengths

🔗 External reference (manufacturer installation guidance example):

https://iwae.com/media/manuals/goodman/glxs4b-installation.pdf

🧰 New vs Existing Line Sets: Can You Reuse Old Ones?

This is one of the most common homeowner questions.

Reusing a line set can be okay if:

-

it’s the correct size

-

it’s clean and uncontaminated

-

it’s compatible with the new refrigerant

-

it passes pressure and vacuum testing

When replacement is smarter

-

changing refrigerant types

-

oil incompatibility concerns

-

visible corrosion or kinks

-

unknown history (especially after compressor failure)

Replacing lines costs more upfront—but can prevent expensive failures later.

🔥 How Refrigerant Lines Are Connected (No Magic Involved)

Most residential systems use brazed copper connections.

What good brazing looks like

-

nitrogen flowing during brazing (prevents internal oxidation)

-

clean joints with even solder flow

-

no burnt insulation or scorched components

-

proper cooling before pressure testing

Bad brazing introduces flakes and debris into the system—something filters cannot fully fix later.

🧪 Pressure Testing: Finding Leaks Before They Matter

Before refrigerant is released, the system should be pressure tested with dry nitrogen.

What this step does

-

verifies tight connections

-

finds leaks before charging

-

protects expensive refrigerant from being wasted

If pressure drops during the test, the leak must be fixed before moving on. Skipping this step is a major red flag.

🧹 Evacuation: Removing Air and Moisture (This Part Is Critical)

Once pressure testing passes, the system must be evacuated using a vacuum pump and micron gauge.

Why evacuation matters

Air and moisture inside refrigerant lines:

-

reduce efficiency

-

create acids

-

damage compressors

-

shorten system life

Evacuation pulls the system down to a deep vacuum and verifies it can hold that vacuum—proof it’s clean and tight.

🔗 External reference (EPA refrigeration service practices):

https://www.epa.gov/section608/stationary-refrigeration-service-practice-requirements

🧊 What “Refrigerant Charging” Really Means

Charging means setting the correct amount of refrigerant in the system—not just “adding some.”

Factory charge (the starting point)

Most outdoor units come pre-charged for:

-

a specific line length (often 15 feet)

-

a specific coil match

If your installation differs (longer lines, different elevation, different coil), the charge must be adjusted.

⚖️ How Technicians Know the Charge Is Right

This is where myths start—so let’s clear them up.

❌ What not to rely on

-

“It feels cold”

-

“The pressures look about right”

-

“This is how we always do it”

✅ Proper charging methods include

-

Weigh-in charging (by scale)

-

Subcooling method (most modern ACs)

-

Superheat method (older or fixed-orifice systems)

Which method is used depends on the system design and manufacturer instructions.

🔗 External reference (refrigerant charging principles – DOE):

https://www.energy.gov/energysaver/maintaining-your-air-conditioner

🌡️ Subcooling vs Superheat (Plain English Version)

You don’t need to calculate these—but understanding them helps.

Subcooling (common in modern systems)

Measures how much liquid refrigerant has cooled below its condensation point.

Used to confirm the system has enough refrigerant, not too much or too little.

Superheat (used in some setups)

Measures how much vapor refrigerant has heated above its boiling point.

Used to protect the compressor and verify correct feed.

If a tech mentions one of these, that’s usually a good sign—they’re following procedure.

🚨 Overcharged vs Undercharged: Why Both Are Bad

Too little refrigerant

-

poor cooling

-

coil freezing

-

overheating compressor

-

higher energy bills

Too much refrigerant

-

high pressure

-

reduced efficiency

-

compressor damage

-

nuisance shutdowns

“More” is not better. Correct is better.

🔥 Special Note on Modern Refrigerants (Like R-32)

Newer refrigerants are more efficient and environmentally friendly—but they come with specific handling rules.

What homeowners should know

-

charging procedures must follow manufacturer specs exactly

-

ignition sources must be controlled during service

-

proper ventilation is required

🔗 External reference (ASHRAE refrigerant safety overview):

https://www.ashrae.org/technical-resources/standards-and-guidelines

This is one reason refrigerant work is usually handled by licensed professionals.

🧾 Documentation: The Most Overlooked Step

A good install leaves a paper (or digital) trail.

Ask for:

-

recorded refrigerant charge amount

-

line set length noted

-

test results (pressure, vacuum)

-

startup readings

This documentation helps with:

-

warranty claims

-

future troubleshooting

-

resale transparency

🚩 Red Flags Homeowners Should Watch For

Be cautious if you hear:

-

“We don’t need to vacuum it long”

-

“It comes charged, so we’re good”

-

“I don’t use a micron gauge”

-

“Pressure test isn’t necessary”

Good refrigerant work is measured, verified, and documented—not rushed.

🧡 Samantha’s Final Takeaway

You don’t need to handle refrigerant yourself to be informed.

If you remember just four things, remember these:

-

Refrigerant lines are not “just pipes”—they’re precision pathways.

-

Line size, cleanliness, and length all matter.

-

Charging is about accuracy, not guesswork.

-

Proper testing protects your system for years, not months.

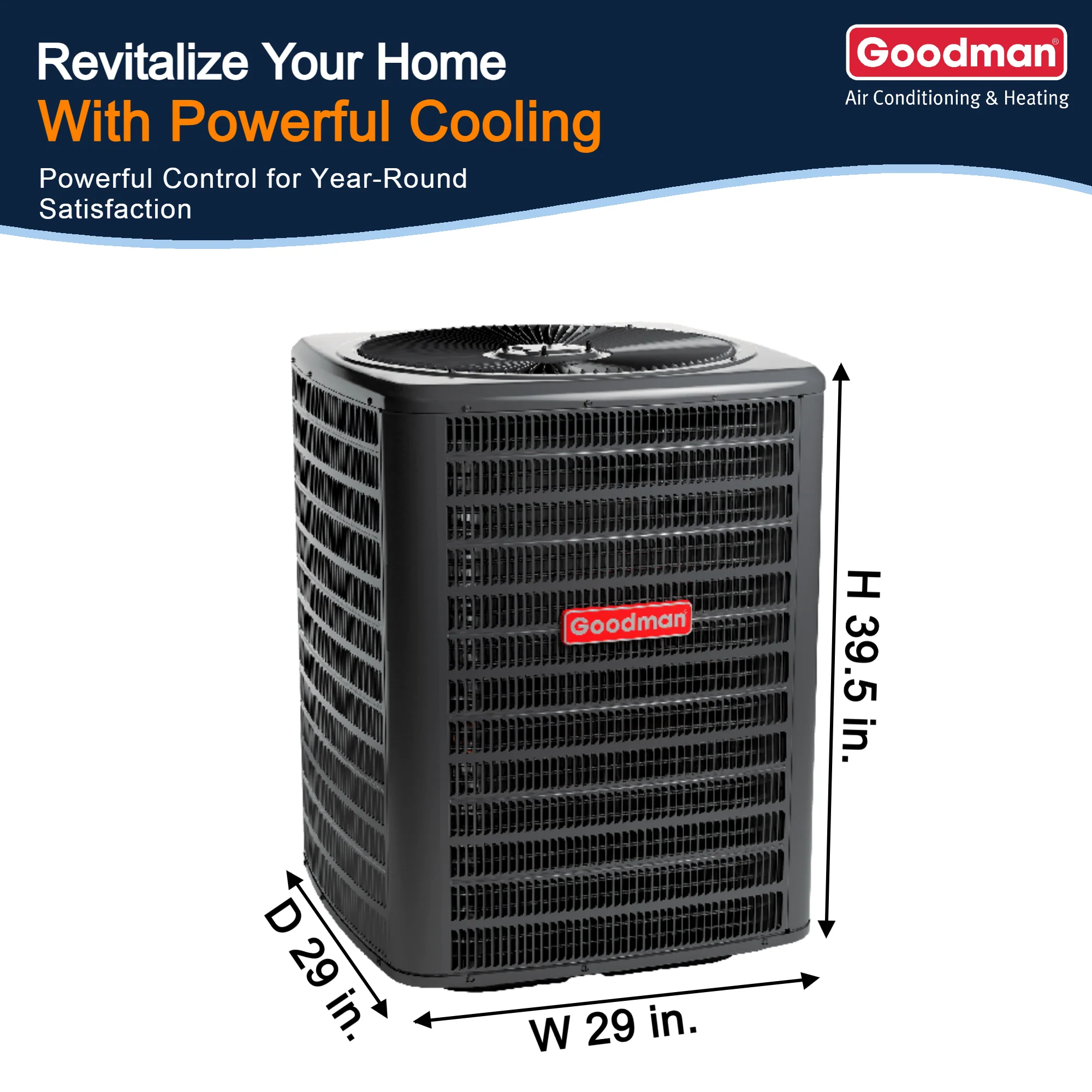

Buy this on Amazon at: https://amzn.to/43doyfq

In the next topic we will know more about: Installing the Furnace & Air Handler: Upflow, Downflow, and Everything In-Between